Charles Critchell

& Rich Lambert

We’ve interviewed academics, practitioners and campaigners from every corner of the globe, as we investigate the ways in which the transport network and urban fabric of different global cities have responded to COVID-19. Our research has taken us from London to Singapore, Detroit, Auckland, Addis Ababa, Bogota and Paris, and has provided us with a unique insight into why some global cities have responded to the urban challenges of the pandemic more effectively than others. Our recommendations are based on extensive and exploratory conversations which, ultimately, aim to understand how we can collectively create more equitable global cities in the months, and years, ahead.

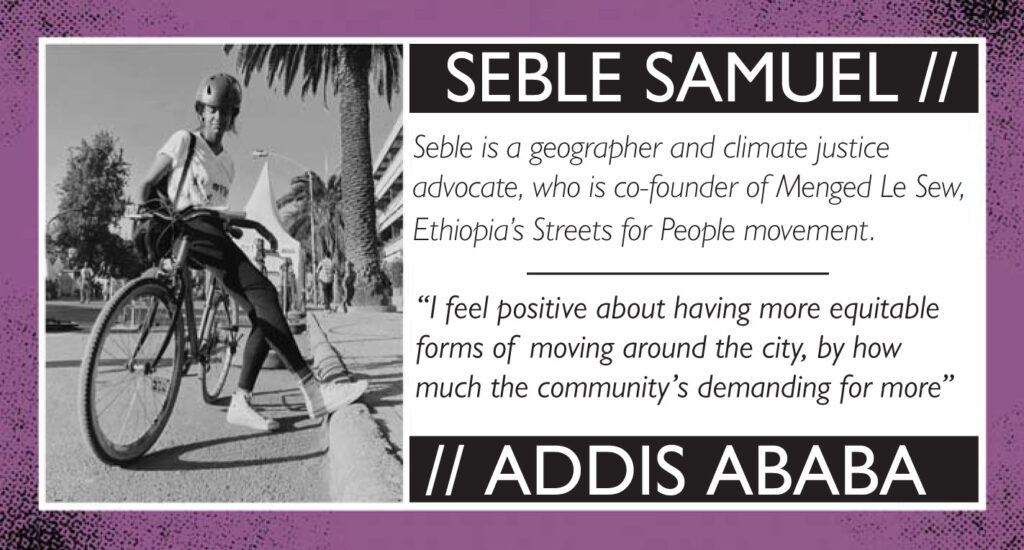

Seble Samuel is an Addis Ababa-based geographer and co-founder of Menged Le Sew, Ethiopia’s ‘Streets for People’ movement. Her organisation aims to make access to urban space more equitable for city users by means other than private car. Menged Le Sew would have held its first country-wide car-free day this year – had COVID-19 not intervened.

Addis Ababa is just one of seven global cities which we have focused on since COVID-19 broke out. While the pandemic has impacted every aspect of daily life, for those residing in cities across the world the situation has been more acute as city space, and people’s access to it, has been fiercely contested.

Global cities are especially prone to the shock of unprecedented events. This is because they are typically denser, better-connected and more diverse, factors which many believe contribute to an increased, and accelerated, spread of disease. Additionally, the proximity of those in global cities when allied with a finite amount of space and the need to socially distance has made the ways in which people travel through their city’s more important than ever.

Many cities have implemented bold measures to enable their residents to carry on as before. They include the installation of emergency cycleways, pop-up sidewalks, and continued access to green space. However, though different global cities have implemented similar measures, why is it that some cities have been able to implement them not only more quickly but more successfully than others, and what does this tell us about how cities may respond to similar events in the future?

Addis Ababa // Africa

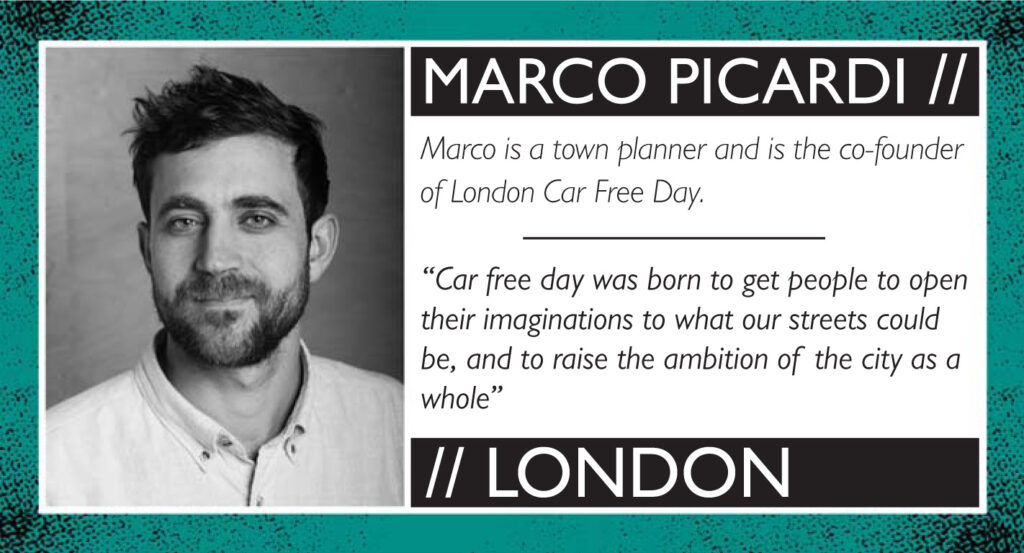

London // Europe

Governance:

Bringing people with you

In their overall response to the pandemic, two global cities, Singapore and Auckland, acted quickly and decisively. In Singapore, Rich Lambert relayed how the city-state “was able to quickly use and implement track and trace…and was able to use a lot of experience gained from previous pandemics”. New Zealand, on the other hand, was “rated as the top country in the world for the quality of its COVID-19 communications”. Auckland-based urban designer George Weeks further suggested that: “experience of biosecurity and a strong civil defence” were factors in enabling New Zealand to respond more effectively than other countries.

While the ability of both Singapore and Auckland to draw upon previous experience was critical, so too were the role of their respective governments and city authorities to effectively communicate their message. This worked to not only inspire confidence in their urban populations but, in turn, enabled city authorities to quickly bring the number of cases down.

Clear communication is born out of clear governance, an advantage enjoyed by a third global city, Bogota. The Colombian capital, led by mayor Claudia Lopez, was able to enforce a city-wide lockdown ahead of the rest of the country, as explained by the city’s bicycle mayor, Pablo Nieto: “The mayor of Bogota is considered the second most powerful politician in the country…while Claudia Lopez is unlikely to be opposed as she elects the mayors for the city’s twenty localities herself”.

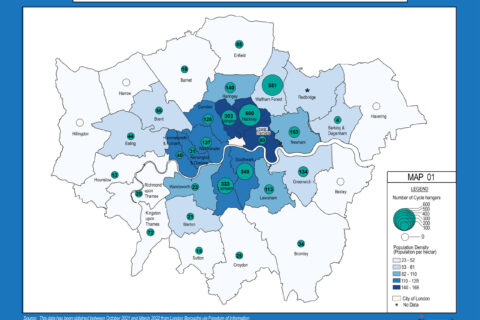

Though many global cities have a mayor, their mandate to govern is often curtailed by forces both above and below them, as has been most apparent in London. London Car Free Day co-founder and town planner, Marco Picardi, attributes the city’s slow response and mixed messaging to a “systematic overlapping patchwork of governance”. This ambiguity has contributed to measures such as emergency cycleways taking weeks, if not months, to implement, whereas comparable schemes have been adopted virtually overnight in Bogota and elsewhere.

Picardi does, however, consider this fragmented political system to have some advantages. This includes the advent of ‘hyper-local’ governance, in which certain London boroughs and neighbourhood groups took the initiative early in the pandemic and implemented social distancing measures, such as coning off roads and filtering streets. Though more formal measures have since been implemented, these early interventions turned the well-established planning protocol of ‘assess, plan and do’ on its head. The new paradigm of ‘do, assess and plan’ is more akin to the principles championed in cities such as Auckland – where quick urban interventions are a staple of the city’s place-based approach.

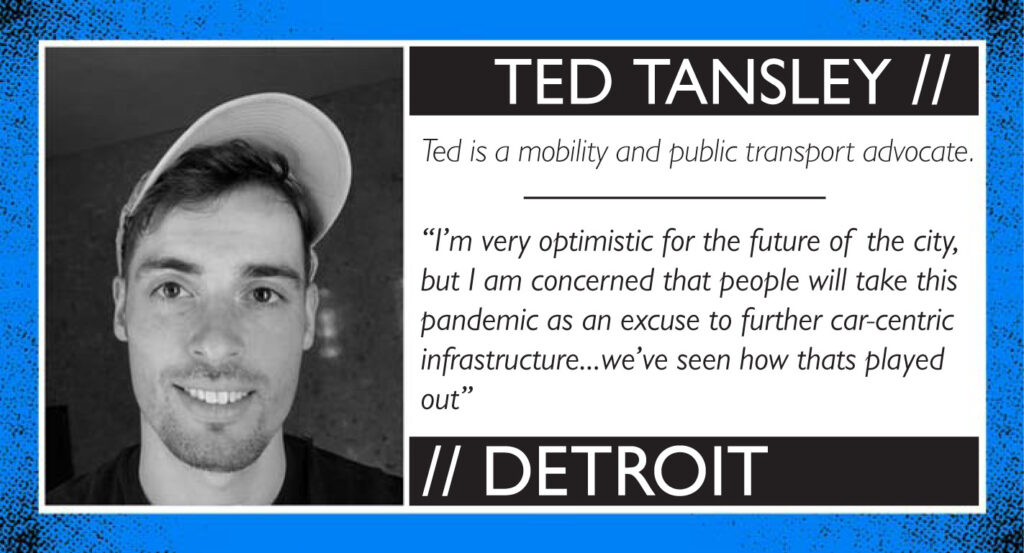

Detroit // North America

The geographic composition of global cities can be understood to be an additional impediment to realising change. Paris-based urban planner, Marion Lagadic, relayed how the Parisian mayor, Anne Hidalgo, must balance the competing priorities of a dense urban core with those of car-dependent outer city suburbs. Detroit, on the other hand, has been hindered by its fiscal capacity to respond to the pandemic owing to the city’s inability to draw upon a wider tax base. This inability, explained Detroit-based mobility advocate, Ted Tansley, is “largely as a result of too many residents living in sprawling suburbs miles from the city’s downtown”.

Space:

Places for people

While the role of city governance has certainly informed the approach of global cities, the tangible actions taken to encourage equitable access to urban space is largely determined by the cultural value each city places upon it. The pandemic has asked tough questions of all of those who live in, work in and visit cities, above all: “What is the role of a city street?”. These are questions which, in the last few months, have led to a range of different answers: answers which will no doubt continue to be defined and redefined in the months and years ahead.

In two global cities, London and Paris, green spaces were temporarily closed off to city residents during their respective lockdowns. In the former, the closing of Victoria Park located in one of the most deprived London Borough’s, Tower Hamlets, provoked an immediate backlash among residents. In the latter, the closure of Parisian parks effectively pushed people into closer contact as groups took to walking around park perimeters, owing to a lack of viable alternatives.

In stark contrast to other global cities, Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, did not enforce a lockdown, as explained by urban academic Biruk Terrefe: “The government realised that a full lockdown was not going to be an option…as too many people are dependent on their daily wage”. Geographer Seble Samuel went on to suggest that people’s use of urban space is intrinsic to the way in which the city operates, and is embedded within the culture of Ethiopian society: “The informal economy is a massive part of city life and much of the work happens in the street”.

Also, unlike other cities, Addis Ababa relocated, as opposed to shutting down, its key city spaces, with the most prominent example being the Merkato Market. The Merkato, the largest open-air market in Africa, was quickly relocated to the edge of the city limits: “There’s not been a full lockdown of these spaces because they are so integral to everyday public life”.

The value of public space in facilitating public life is perhaps best encapsulated on Bogota’s streets. Since 1974, the city has hosted the monthly Ciclovia, literally translated as ‘cycleway’, a world-renowned event which has come to represent much more than the ability to cycle the city’s streets, unencumbered by motor traffic.

Bicycle mayor Pablo Nieto explained that the Ciclovia was “born as an appropriation of the city’s streets” while, even today, it is embedded within the very culture of the city and its people. This, he believes, was another reason that the city was able to rapidly build 80km of emergency cycleways in response to the pandemic: “It’s the culture of the bicycle…people accept the cycleways in a way that they perhaps do not in other countries”. These are temporary cycleways which, incidentally, are set to become permanent.

Bogota // South America

Drawing upon the Ciclovia for inspiration, Addis Ababa’s Seble Samuel has moved quickly to position Menged Le Sew, the Ethiopian Streets for People initiative, at the forefront of the country’s non-motorized transport movement: “We want to influence people’s behaviour and how the city is planned”. Growing, the car-free movement will undoubtedly require strong political backing to effectively deliver change, though this is something which the geographer is optimistic can happen in the post-pandemic days which lie ahead.

The combination of political will, and the ability to be able to deliver upon it, is perhaps most evident on the streets of Singapore. The Southeast Asian city-state has invested heavily in its urban space – chiefly because it is so limited. Urban practitioner Rich Lambert explained that part of this urban strategy has been the development of the Park Connector Network. The 300km web of green infrastructure, including paths and cycleways, has been used heavily by residents throughout the course of Singapore’s lockdown. More fundamentally, the need to deliver a high-quality built environment is an aspiration which has been apparent since Singapore gained independence, more than fifty years ago.

Unlike Singapore, Auckland only recently began to prioritise the quality of its urban space as in the mid-2000s, the city authorities finally acknowledged that its built environment was uniformly lackluster. In the intervening decade, the city’s politicians and design professionals have worked hard to co-create an innovative design culture, which culminated in the founding of the Auckland Design Office, or ADO, in 2014.

George Weeks, a principal ADO urban designer, believes that one of the office’s greatest successes has been the deployment of tactical urbanism in, or more accurately on, the city’s streets. Tactical urbanism, as described by Weeks, is a “lighter, quicker and cheaper” way of temporarily changing a city’s streets, primarily for the benefit of pedestrians. Measures can typically include painting, adding planters or building up pavements, measures which, since the start of the pandemic, have proved indispensable in providing more space for pedestrians in which to socially distance.

While socially distanced footways were high priorities in the early days of the pandemic, the focus has now shifted toward getting city economies moving again, which includes creating additional space for bars and restaurants to seat and serve customers. In this respect, Paris has led the way as the city’s recently reelected mayor, Anne Hidalgo, passed a measure on June 2nd which enables bars and restaurants to extend their terraces to safely accommodate more customers.

Underpinning City Hall’s drive to re-appropriate urban space are Hidalgo’s dual aims of reducing car dependency and, in turn, creating more cycleways in the city: “Her strategy has been very much focused on developing cycling in Paris…through a doubling of cycle path kilometers via her very ambitious ‘Plan Velo’”. Urban planner Marion Lagadic further asserted that another of Hidalgo’s goals is to “redesign all of Paris’ streets as cyclable by 2024”. All this would suggest that the incumbent mayor has set a very clear path for the city – one which targets the Paris 2024 Olympics, just four years from now.

Singapore // Asia

Auckland // Oceania

Trajectory:

Getting, and staying, on track

Paris’ ambition to become a great cycling city can be linked to the hosting of the 2024 Olympics. Though the previous mayor, Bertrand Delanoe, had made cycling more acceptable and, in turn, car-use less acceptable, it is Hidalgo who has thrust the city onto its current short, sharp trajectory. Paris, however, is not alone. Arguably, the global cities which have proved most resilient to the urban shock of the pandemic are those which are on their own unique trajectories, while others, including London and Detroit, have seemingly struggled to define and apply their urban vision.

The city on the longest trajectory is Singapore. The modern-day city-state was founded in 1965 and soon became recognized as one of the vaunted Asian Tigers as it prioritizes economic growth, long-term planning, political stability and quality of life for its residents. This can be seen in its high-quality state housing, world-leading public transport, and extensive green infrastructure. These advantages, when allied to its previous experience of pandemics, look set to position the city-state well post COVID-19.

On intermediate trajectories are Bogota and Addis Ababa. Beginning in the mid-1990s, successive and innovative Bogota mayors have built on each other’s work to not only make the city safer, but to invest widely in both public transport and the development of one of the world’s most extensive cycle networks. The benefit of such an embedded cycling culture encouraged the city to quickly install emergency cycleways, while the autonomy of the mayor enabled her to effectively lockdown ahead of the rest of the country.

Approximately ten years later, in 2005, the Ethiopian government began to invest heavily in pro-poor infrastructure in the capital, Addis Ababa. The period marked the beginning of a developmental state based on that of the Asian Tigers, an approach which soon encouraged the country to push for the attainment of middle-income status by 2025. Alongside the development of the city’s formal economy, the city’s nuanced approach in dealing with the pandemic has enabled public spaces, and the city’s informal economy, to carry on unabated as it has thus far avoided a full lockdown.

On the shortest trajectories are Paris and Auckland. Paris, with its stated goal of ‘redesigning all streets as cyclable by 2024’, has drawn heavily on strong leadership and resolute political will. Contrastingly, Auckland’s ability to improve the quality of its built environment has, in large part, been due to its more collaborative governmental approach. Structural changes, which have involved Auckland shedding layers of bureaucracy, have enabled it to redefine itself as the Southern Hemisphere’s largest unitary authority back in 2010. This provided city-run departments, including the ADO, the mandate to deliver impactful projects, which have led to genuine improvements to civic life.

Arguably, the unifying feature which all these cities enjoy in enabling them to better respond to COVID-19 is their ability to employ ‘further’ as opposed to ‘forced’ experimentation. This has essentially allowed them to continue doing the things they were successfully doing prior to the pandemic. Examples include Singapore’s investment in green infrastructure, Paris and Bogota’s use of the bicycle and Auckland’s accelerated use of tactical urbanism.

Encouragingly, other cities, including London and, to a lesser extent, Detroit, are now catching up. In May, the UK capital began rolling out emergency cycleways and pedestrian squares as part of its Streetspace plan, while boroughs have since been bidding for funding to implement local measures. However, both ambiguous messaging and inconsistent application has impacted the city’s ability to move both further and faster, a real worry now that the lockdown has eased, and many streets are once again choked with cars.

Fare City recommendations:

A call to action for global cities and their residents

Though the trajectory of some global cities has enabled them to mount a robust urban response to the pandemic, the dangers inherent in quicker trajectories can also lead to growing pains. In Auckland, the sudden surge in the city’s diesel bus fleet following re-regulation in 2013 has put the now extensive network at odds with the city’s C40 commitments. The fleet, far from retirement, is a major source of air pollution in the city center and will likely have to be phased out sooner than was originally planned.

More alarmingly, Addis Ababa’s prioritisation of pro-poor infrastructural investment – social housing, electricity, and accessible transport – has seemingly stalled since the 2018 national elections. The emergence of high-end real estate projects, targeted at tourists and urban elites, endeavors to increase city land values and generate revenue for the benefit of the few and not the many. This is the emerging reality in the country’s capital as it races towards achieving middle-income status by 2025.

Even though global cities are, indeed, more prone to the shock of unprecedented events, they are also better equipped to deal with them. Innovation, agility and resilience all enable global cities to respond to crises, regardless of the trajectory which they find themselves on. The following recommendations are, therefore, aimed at city authorities, neighbourhood organisations and city users alike. If nothing else, the pandemic has surely underlined that any great global city is the sum of each and every individual that contributes to making it so.

Experimentation is empowering:

The pandemic has required every global city and its inhabitants to experiment. These experiments have included city authorities delivering new active travel programmes, local shopkeepers appropriating urban space for customers, and city users being free to explore ordinarily gridlocked streets. The pandemic has challenged people’s understanding of urban space and invited them to reimagine how it could be used. Though life in many global cities is returning to a semblance of normality, Fare City encourages city users and authorities to continue to pursue further experimentation. This includes identifying, and utilising, the small opportunities which urban spaces present, for both personal gain and the wider public good.

Places for people:

The coming together of communities to collectively support one another has been a key feature of the pandemic. It has been local communities, with a grasp of local issues, which have exhibited the engagement, endeavor and empathy required to shape the world’s post-pandemic cities. Fare City calls upon city authorities to reciprocate and to position people at the heart of how cities are designed, and how their streets and spaces are used.

Consistent communication is key:

Consistent communication is crucial in enabling city authorities to inspire confidence in their urban populations. Cultivating a level of trust between city and citizen typically provides a mandate for city authorities to go both further and faster. This symbiosis is critical in enabling cities to launch and sustain their urban trajectories, which facilitate greater resilience and certainty in dealing with unprecedented events. Fare City advocates that city authorities leverage the unique circumstances of the pandemic to strengthen, or alternately develop, their city trajectories with the aim of realising greater accessibility, equity, and sustainability for their inhabitants.

Fare City would like to thank all interviewees who kindly gave up their time to participate in this study. More details about the interviewees and their work can be found here. We would like to credit the following people for contributing their images for the article: Nafkot Gebeyehu, Menged Le Sew, Ted Tansley, Ricardo Rodriguez, Rich Lambert, George Weeks, Jean-Charles Maurice.

Article design by David Maguire

Paris // Europe