The young boy, his face creasing into a frown, was anxious to remind his mum that he did have asthma and that fewer cars would be a good thing. “Yes, you’re right”, the mum conceded, before changing her mind and replying that, having initially been in favour of reopening the bridge to all vehicles, she now favoured public transport, cyclists and pedestrians only.

This was just one of the 120 or more interviews which Fare City recently conducted regarding the closure of London’s Hammersmith Bridge to motorised vehicles. Not only did the results of the survey suggest that bridge users recognised a range of benefits as a result of this part closure, but that respondents were also open to alternatives for how the bridge could be used in the future.

That future is to be decided by the London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham, which owns the bridge. The council, working alongside Transport for London, which operates the bridge as part of its Strategic Network, has reaffirmed that it will be re-opened within three years and restored “to full working order and to its Victorian splendour”.

Despite the council’s proclamation there remains much uncertainty; not least as to who will foot the bill for the repair work. Given the geography of the bridge – straddling the Boroughs of Hammersmith and Fulham to the north and Richmond to the south – there has been much wrangling from those at all levels of the political spectrum. One thing that is certain is that the bridge does need to be repaired, though is reopening it to all modes of transport really the only option?

Wellbeing benefits

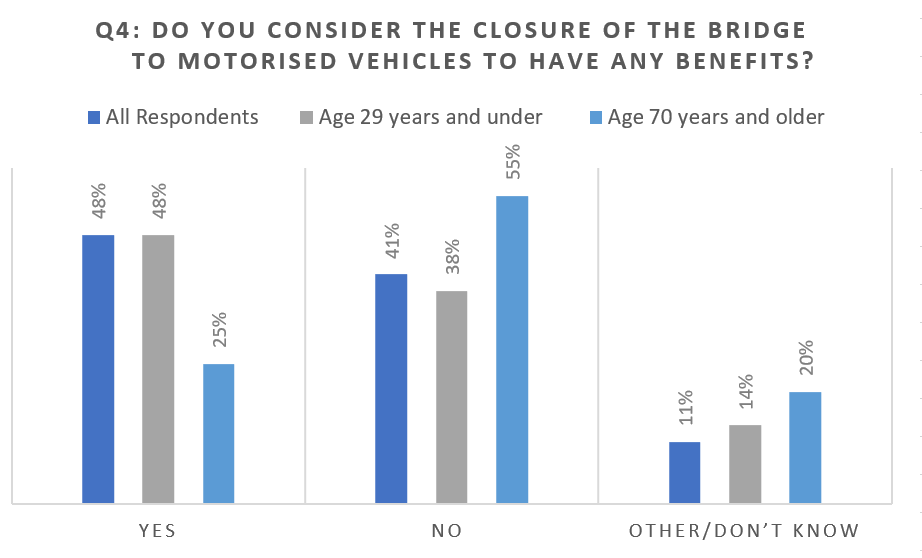

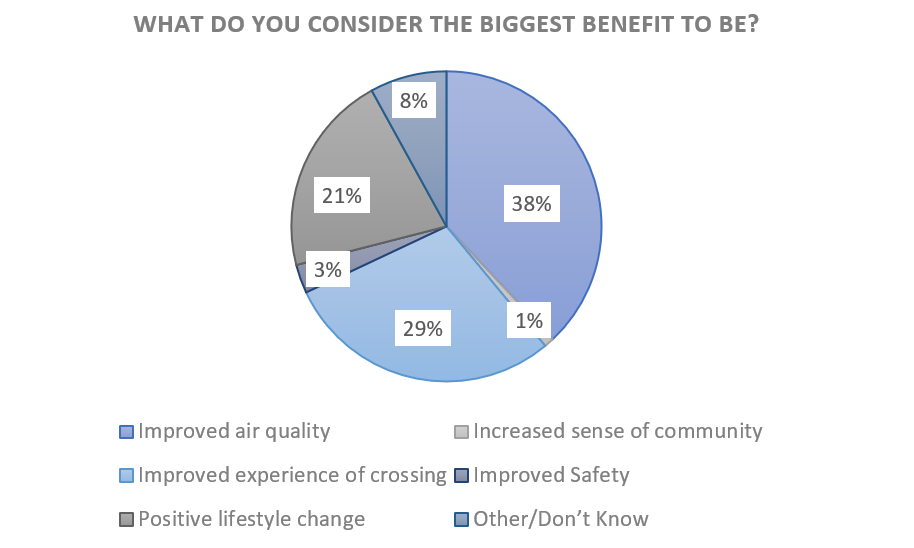

Whilst it cannot be denied that the closure of the bridge to motorised vehicles has had a negative impact on some, a greater number of those surveyed (48 per cent), acknowledged that it did bring some benefit. One Barnes resident reflected that the bridge “feels very natural as it is”, whilst an elderly lady confided that “before I felt nervy crossing on foot, with vehicles constantly going past”.

Those who believed that there were some benefits cited improved air quality as being the single biggest (38 per cent). Others believed the biggest benefit was an improved experience of crossing the bridge (29 per cent), whilst one in five (21 per cent), identified that the closure of the bridge to motorised vehicles had encouraged a positive lifestyle change.

A young couple explained that, although the closure of the bridge to motorised vehicles meant ordering a takeaway, or getting an Uber after a night out was problematic, it had encouraged them to make positive lifestyle choices. “Yes, we’re trying to cook and he’s definitely walking more now”.

48% – The percentage of respondents who consider that the closure of the bridge to motorised vehicles does have some benefit

“We have to provide for the elderly”

A car-free future?

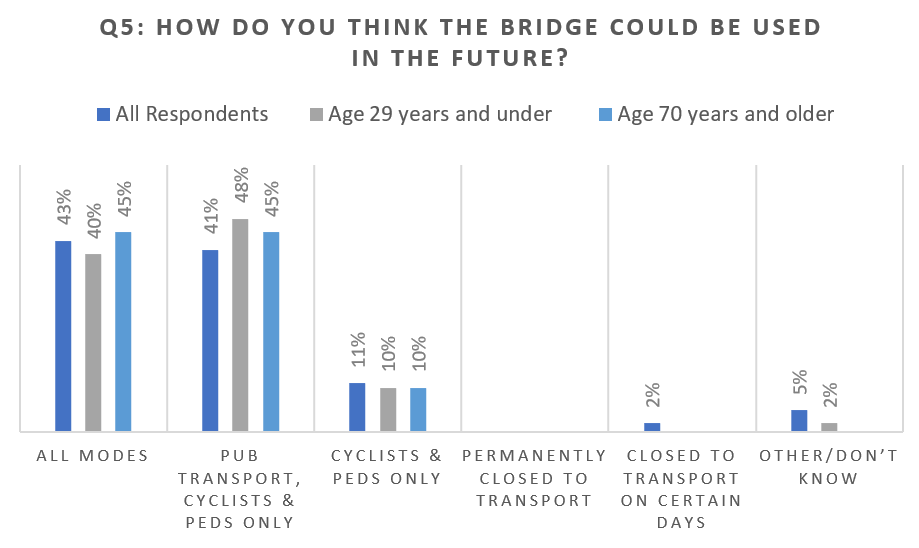

Foregoing luxuries such as taxis and takeaways may not resonate with those who depend on the bridge for essential day to day activities, although the way in which respondents want the bridge re-opened in the future just might. Almost as many respondents (41 per cent), believe that the bridge should be reopened to public transport, cyclists and pedestrians only, as those who believe it should be reopened as it was previously used (43 per cent).

The former choice was the preferred option (48 per cent) among those aged 29 years and under. One teenage girl explained that, although re-opening the bridge to cyclists and pedestrians only was her first choice, she believed that it was public transport which would help “provide for the elderly”.

Despite no overwhelming consensus among respondents, there is, however, a clear need to provide some form of public transport in the short-term. At present a solitary E-pedicab, operated by shared transport provider Ginger, is plying the north-south route and is proving popular with bridge users.

Joseph Lagden, Ginger’s Operational Manager, states that the companies E-pedicab is currently completing “50 – 60 journeys a day, and that the majority of these journeys are for customers that may not have made it over the bridge without the service”. From customers needing to go to the hospital or to the GP across the bridge, to those wanting to bring their shopping back from Hammersmith, there is certainly plenty of demand for a service hailed as a “godsend”, by one lady who was surveyed.

Whilst this community minded start-up has taken the initiative which has at least led to bridge users having an option, it does beg the question – what are the authorities doing about the situation? The answer is not a lot. Although TfL have recently announced a Dial-a-Ride service for the most vulnerable residents who live within a mile of the bridge, there seems to be little else by the way of alternatives for everyone else.

With the winter fast approaching, Ginger are planning to have two E-Pedicabs running simultaneously by the end of November. This is in addition to an online booking service and E-pedicab infrastructure in the form of seats and shelters. Given Hammersmith & Fulham’s projected 3-year time frame for the re-opening of the bridge, the authorities will have to up their game.

A recent update from TfL has confirmed that in addition to re-opening the bridge to all modes of transport, it will continue to ‘limit the flow of buses on and off the bridge’ which they consider necessary to ‘prevent future damage’. Regular bridge users will no doubt recollect that this is the tactic which was previously trialled, and which previously failed, owing to TfL’s inability to regulate the number of buses on the bridge at the same time.

There is a real need to consider new forms of sustainable – and high capacity – public transport for when the bridge reopens, in addition to permanently closing it to cars. Many respondents suggested smaller electric buses, whilst others are clearly concerned that returning to a high-volume traffic flow, is a threat to the future of such an iconic structure.

Raising Ambitions

It is this appreciation of the bridge as an iconic structure, which has arguably only become more apparent since its closure to motorised vehicles. Though pedestrians must stick to walkways either side of the carriageway, it is not hard to imagine the bridge fully pedestrianised. One respondent seemed to echo the thoughts of many; stating that the bridge had the potential to become a “sublime public space”.

When respondents were asked whether they could see any benefit for the use of the bridge as a community market one day a month, three quarters (76 per cent), answered yes. This figure rose to 8 out of every 10 respondents (83 per cent), of those aged 29 and under. Two boys suggested that “a market would bring the two sides of the bridge together”, whilst a nineteen-year-old beamed that a street performance space “would be next level”.

“The bridge has the potential to become a sublime public space”

“Three quarters,76%, of all respondents considered that the use of the bridge as a community market, one day a month, would provide some benefit.”

Indeed, there are precedents for the re-appropriation of bridges as new public spaces. Perhaps the most well-known is the Széchenyi Chain Bridge in Budapest, designed by the English civil engineer William Tierney Clark. Incidentally, this is the same engineer who designed the first Hammersmith Bridge – the pier foundations of which the current bridge resides on. On Sunday’s, during the summer, the Széchenyi Bridge is often closed to vehicles as it hosts an open-air market, an event which continues to prove popular with locals and tourists alike.

More broadly, the re-appropriation of vehicular city streets as new public space, is very much at the forefront of the urban agenda in cities across the globe. Just last month London held its first Car Free Day which co-founder, Marco Picardi, believes is the result of a “growing global recognition that our streets can play a role in helping our cities adapt to climate change, help improve resident’s health, and provide new amenities for people”.

New amenities in the form of a community market on Hammersmith Bridge may form part of Picardi’s call for London to “raise its ambition”, and for members of the public to “reimagine what and how they want their streets to be”. Although the wheels are already in motion for motorised vehicles to be rumbling over Hammersmith Bridge within three years, it seems that true to Picardi’s sentiment, the young are already imagining alternative ways in which this iconic structure could be enjoyed by future generations.